The Open Gardens Festival is a unique cultural and social event that not only revitalizes public spaces but also strengthens interpersonal bonds, promotes local historical, cultural, and natural heritage, and fosters the harmonious development of the local community. In an era of fast-paced life and growing social distance, such an event becomes a rare opportunity for meaningful meetings and conversations, sharing interests, and establishing valuable collaborations. By opening their gardens, neighborhood residents invite their neighbors and guests to co-create a space filled with culture, art, knowledge, craftsmanship, as well as joy, fun, and the beauty of their plant arrangements. The festival serves as an excellent way to promote local talents and showcase the history and traditions of one’s own place on Earth. It also provides an opportunity to build good neighborly relations, strengthen the sense of security in the immediate environment, and cultivate a habit of mutual support in everyday life. Moreover, it encourages greater engagement in public affairs for the common good. The ability to bridge social divisions and restore a sense of community is one of the most valuable aspects of the Open Gardens Festival.

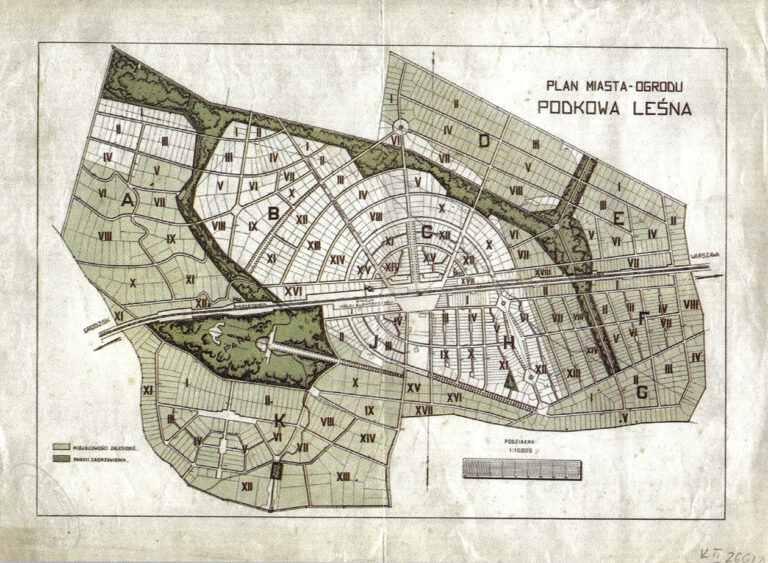

The tradition of opening private gardens, similar to other European countries, began to spread in Poland at the beginning of the 21st century, drawing inspiration from both native gardening traditions and foreign models. The first Open Gardens Festival was held in 2005 in Podkowa Leśna, a town with a villa-like, historical, and garden character, perfectly suited to the idea and spirit of the event. The first edition of the festival was combined with the celebration of European Heritage Days. Its success led to similar initiatives emerging in neighboring towns such as Brwinów, Milanówek, and Konstancin-Jeziorna. With each edition, the festival attracted increasing interest from residents. In the following years, the number of open gardens steadily grew, not only in suburban Warsaw but also in other regions of Poland.

European Garden Tradition

The roots of the modern European concept of open gardens can be traced back to the tradition of English landscape gardens, which began to play a significant role in the culture and architecture of many countries at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. The idea of opening them to a wider audience was inspired by earlier aristocratic court practices in France, England, and Germany during the 17th and 18th centuries[1], where parks and gardens were made accessible to high-society guests. Unlike the geometric Baroque gardens of France[2], English landscape gardens[3] gained particular popularity during the Romantic era.

During the Enlightenment, France under Louis XIV, Louis XV, and Louis XVI was the cultural model for all of Europe. French Baroque gardens, such as those surrounding the Palace of Versailles or the royal Château de Meudon, symbolized order, control, and the power of absolute monarchy. After 1815, following Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo[4], France lost its dominance to England, which influenced various cultural trends, including garden design. The new era of Romanticism rejected the rigid symmetry of classicism[5], promoting freedom, nature, and emotion. The British lifestyle became fashionable across the European continent. Unlike French gardens, English gardens were asymmetrical, naturalistic, and inspired by the wild landscape, which better suited the spirit of Romanticism. They were also cheaper and easier to maintain, as well as more open to visitors. Their accessibility was linked to the development of the gardening movement and the tradition of organizing charitable events.

The modern European tradition of open gardens began in 1927 in the United Kingdom with the establishment of the National Gardens Scheme.[6] This initiative aimed to raise funds for healthcare by allowing the public to visit private gardens for a symbolic fee. The idea quickly gained popularity, and the number of participating gardens steadily grew, fostering the promotion of horticulture, the exchange of experiences, and the integration of green-space enthusiasts. It also served as an inspiration for other European countries, particularly those with a strong tradition of opening private gardens for community-oriented events.

In the second half of the 20th century, the concept of open gardens evolved in various forms, especially in Western Europe. During the 1980s and 1990s, initiatives similar to the British model emerged in France, Germany, and the Netherlands, often combined with heritage conservation and environmental education. The culmination of this trend was the establishment of the Rendez-vous aux jardins festival in France in 2003.[7] Organized by the French Ministry of Culture, the festival aimed to popularize garden art and landscape heritage by opening hundreds of private gardens and public green spaces. In the following years, the event expanded to more than twenty countries, including Poland, becoming a permanent part of Europe’s cultural landscape in 2018.[8]

Polish Garden Tradition

In historical Poland, there was no tradition of organizing open gardens in the same way as in France, Great Britain, or Germany. However, certain elements of this idea can be found in the history of Old Polish noble culture. As early as the Renaissance and Baroque periods, owners of Polish palaces and manor houses made their gardens accessible to their guests. The gardens of the Royal Łazienki, Wilanów, Nieborów, and Arkadia were partially open to local communities as well. This stemmed from the belief in the necessity of educating and raising the cultural level of society. Opening gardens to a wider public was an expression of patronage for culture and art, as well as modern thinking, particularly among more progressive aristocrats[9] such as King Stanisław August Poniatowski or the Czartoryski family.[10]

During the 19th and 20th centuries, due to social, economic, and urban transformations, more and more private gardens came under the ownership of cities or public institutions. With the rapid growth of cities, the demand for green spaces accessible to the general public increased, leading many former aristocratic gardens to be transformed into city parks or botanical gardens. The decline of the old elites—especially due to uprisings, wars, and political changes—led to the confiscation or sale of estates, which often passed into the hands of the state or cultural institutions. At the same time, the development of the “garden city” concept[11] and a growing conservation awareness meant that historic gardens became part of the national heritage, subject to protection and opened to the public. The high maintenance costs of extensive private parks also became a burden for their owners, prompting them to donate land for public use. As a result, many historic gardens, once accessible only to a narrow elite, became public spaces serving recreation, education, and nature conservation.

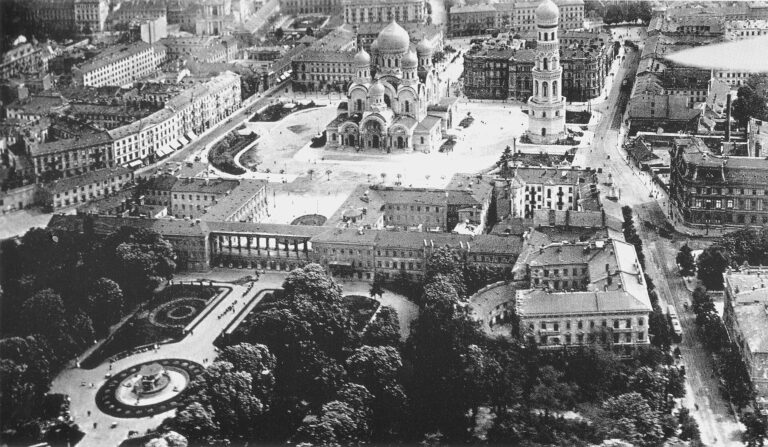

Such was the case with the Saxon Garden in Warsaw, which, in 1727, became the first public park in Poland and one of the first in Europe—open to everyone, not just the aristocracy. King Augustus II the Strong’s decision to make the Saxon Garden accessible to Warsaw’s residents aligned with the Baroque idea of creating representative urban spaces and gradually opening royal residences to the entire society. Initially, the Saxon Garden served as a strolling and recreational area, inspired by the French style. In the 19th century, following a broader European trend, it was redesigned into a romantic English landscape garden, and today it remains a unique blend of both styles.[12]

Similar transformations in urban greenery took place in 19th-century Kraków. The Kraków Planty, created between 1820 and 1830, were intended to serve a function similar to that of the Saxon Garden in Warsaw. The Planty were formed by transforming the city’s old fortifications—where a moat and demolished defensive walls once stood, a green belt was created around the Old Town. From their inception, the Planty were a public space accessible to all. They were meant to serve representative, recreational, and sanitary purposes, eliminating neglected ruins from the urban landscape and giving the city a modern character. They also marked a natural boundary between Kraków’s historic center and its expanding suburbs. The Kraków Planty are one of the earliest examples of deliberate urban green space planning in Poland.[13]

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, new urban and social ideas increasingly influenced the shaping of green spaces. Gardens began to play an ever-greater role in the lives of urban and suburban communities. Inspired by Western European models, gardens were created in both large and small Polish cities, as well as in noble manor estates. During this period, the idea of making private gardens available for social gatherings and cultural events became popular, serving as a prelude to the much later development of “open garden” concepts. The growth of cities was accompanied by an effort to provide residents with access to parks and squares, which had not only aesthetic but also health and recreational benefits. During this period, the first allotment gardens appeared[14], allowing city dwellers to grow plants and relax outdoors. Public botanical gardens and parks, modeled after Western designs—such as Ujazdowski Park in Warsaw[15] and Stryjski Park in Lviv—also gained popularity.[16]

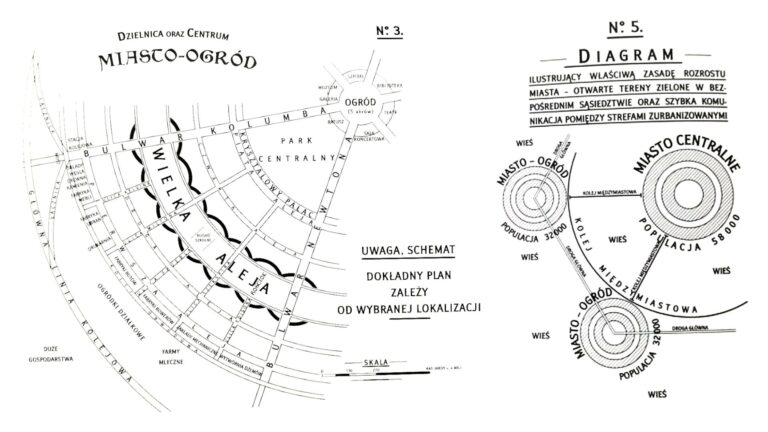

The interwar period saw further development of urban greenery and efforts to integrate gardens into city planning. During this time, modern city parks were designed, such as Skaryszewski Park in Warsaw[17], which combined elements of romantic landscape design with functional recreational areas. Inspiration was drawn from Ebenezer Howard’s “garden city” concept.[18] Gardens around villas and manor houses often blended elements of the traditional Polish landscape—such as linden alleys, orchards, and flower gardens—with modern spatial solutions. In pre-war Poland, gardens and green spaces played a vital role not only as places of leisure but also as symbols of national identity and cultural heritage.

Ebenezer Howard’s garden city concept, developed in the late 19th century, aimed to create harmonious spaces that combined the advantages of urban and rural living. Howard sought to improve the living conditions of the working class by offering an alternative to overcrowded and polluted industrial cities. His vision included self-sufficient cities surrounded by greenery, providing residents with access to workplaces, services, and recreational areas. The first implementations of this idea, such as Letchworth Garden City (1903) and Welwyn Garden City (1920) in England, were early attempts at putting these principles into practice. In reality, garden cities often also attracted the middle and upper classes, which deviated from the original intention of creating spaces primarily for workers. Contrary to later interpretations, garden cities were not designed as enclaves for the aristocracy or intellectuals but as self-sufficient communities organized cooperatively to ensure equal access to living spaces and reduce social disparities.

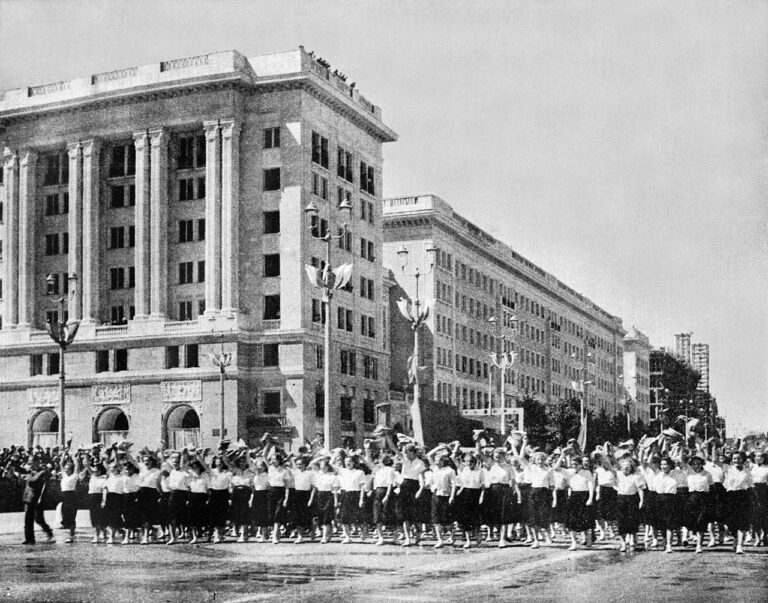

During the period of the Polish People’s Republic (PRL)[19], old garden traditions underwent significant changes due to political pressures, transforming under state policies that subordinated green spaces to ideological and functional goals. During this time, workers’ allotment gardens were developed[20], intended to provide city residents with access to greenery and the opportunity to grow vegetables and fruits for personal use. The idea of communal garden use also persisted through the activities of horticultural cooperatives[21], the creation of neighborhood green spaces—often as part of so-called “social labor efforts”—and the organization of outdoor festivals. Opening green spaces to the public was part of a broader movement promoting a collective lifestyle, but it took place under strict state control.

The state dictated the shape of urban greenery, often integrating it into central urban planning schemes, which led to uniformity and rigidity in design. Many historic parks and gardens were opened to the public, but at the same time, numerous private green areas were repurposed for non-garden functions, such as residential development or public infrastructure. While government policies supported the maintenance and expansion of recreational spaces, they also restricted individual initiatives and private garden ownership, favoring collectivized solutions. As a result, many historic gardens and parks deteriorated, and the preservation of landscape heritage was subordinated to social and economic needs, often at the expense of their original aesthetic and cultural values.

After the period of PRL collectivization and nationalization—which limited private land ownership and traditional ways of using space—the idea of open gardens began to revive with the return of private property and social self-organization within local government structures. The political transformations after 1989 enabled the gradual rebuilding of traditional gardening practices and the rediscovery of open garden ideas as spaces for social gatherings and cultural creation. In the 1990s, Polish social movements flourished, promoting small-scale forms of community integration inspired by Western models such as the National Gardens Scheme, Rendez-vous aux jardins, or Tag der offenen Gärten.[22]

As a result of these efforts, the Open Gardens Festival was initiated in Podkowa Leśna in 2005, inspiring other cities and towns. This unique initiative allowed private gardens to once again become spaces open to local communities, integrating the open garden concept into a broader context of national cultural revival and rebuilding social bonds after decades of centralized control and societal fragmentation under state-managed structures.

Degradation of National Heritage During the Polish People’s Republic (PRL)

A fundamental feature of the communist regime in Poland during the PRL era was the elimination of private property and totalitarian state control over all aspects of life. After World War II, the communist authorities took over many private properties under the land reform of 1944[23] and decrees issued by the puppet president, dependent on the Kremlin, Bolesław Bierut.[24] Noble manors, villas, and tenement houses were often confiscated from their owners and transferred without compensation to the people’s state, which waged an ideological and armed struggle against the former elites. The new authorities consistently sought to eradicate all traces of the former aristocracy and bourgeoisie, replacing them with new party and political elites.[25]

The nationalization of properties during communism was part of a broader strategy to eliminate Poland’s pre-war cultural heritage. In addition to individual buildings, it also affected extensive urban layouts, historic districts, parks, gardens, and green spaces. The communist authorities aimed to erase traces of the old social structure and eliminate private property, which ultimately led to the devastation of many elements of national material and natural heritage. The modernization of cities resulted in severe distortions or the complete destruction of their historical character. An example is Warsaw, where, after World War II, the pre-war street grid was not restored in many areas, and historic tenement houses were not rebuilt, with residential blocks and road arteries taking their place. In cities such as Wrocław, Gdańsk, and Poznań, historical spatial divisions were often ignored, replaced by plans based on Soviet urban models.[26]

The policies of the communist authorities in Poland also had a significant impact on suburban garden cities near Warsaw, such as Podkowa Leśna, Komorów, Milanówek, Brwinów, and Konstancin-Jeziorna. These towns, designed as exclusive enclaves of greenery and harmonious architecture, were largely degraded due to post-war nationalization, collectivization, and urban transformations imposed by the new authorities. Before World War II, they were primarily inhabited by intellectuals, scientists, artists, and professionals. After the war, many of these houses were taken over by the state under nationalization decrees. Large villas were divided into smaller communal apartments, and their original owners were often forced to leave or share their living space with tenants assigned by state authorities.

The suburban garden cities, as well as similar towns in other regions of Poland, were designed as places where architecture coexists harmoniously with nature. During the PRL era, many former gardens and green areas were destroyed. Authorities often ignored historical urban layouts, neglected park architecture, and allowed random construction projects that disrupted the aesthetic character of these towns. In some cases, the division of large plots into smaller ones and increased construction density led to the loss of their original spatial and natural character. One example is Konstancin-Jeziorna. Before the war, it was considered a prestigious summer resort, but during the PRL era, it underwent significant transformation. Many former residences and villas were taken over by the state and converted into sanatoriums, vacation centers for state institution employees, or orphanages. While some of these functions helped preserve old buildings, in many cases, a lack of maintenance and years of neglect led to their ruin.

The policies of the communist authorities ultimately led to the complete degradation of most garden cities across Poland. Although some, such as Podkowa Leśna and Konstancin-Jeziorna, retained parts of their pre-war character, many former residences were destroyed or altered in ways that erased the original urban and architectural concepts of these towns. It was only after the fall of communism that a gradual restoration of their historical character became possible. This process has been aided by numerous grassroots initiatives undertaken by local residents through associations and individual projects. One such grassroots initiative is the Open Gardens Festival.

Preservation of National Heritage

After the fall of the communist regime in Poland, one of the most important challenges was the protection and restoration of national cultural heritage. During the communist era, many historic buildings were left unrestored due to political, ideological, or financial reasons. It was only after the political transformations of the late 1980s and early 1990s that large-scale efforts began to restore and revitalize historic sites. The collapse of communism opened new possibilities, both in terms of funding availability and a shift in the approach to national heritage. The end of the communist era removed ideological barriers to financing monuments associated with the former elite and monarchy. The introduction of a market economy enabled the inflow of private funds, the involvement of sponsors, and the acquisition of foreign financial support.

Significant changes were also made to spatial planning laws, which had a substantial impact on the protection of cultural heritage.[27] These changes were part of a broader transformation process, shifting from a centrally planned economy to a market-based model and decentralizing power. In this transformation, both domestic and international institutions played a key role, providing financial, expert, and organizational support. At the same time, public awareness of the importance of national heritage grew, leading to increased support for initiatives aimed at restoring and conserving historical sites. Thanks to these changes, many symbolic landmarks of Polish culture were able to regain their former glory.[28]

The protection of Polish cultural heritage was taken up by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, the National Institute of Heritage, and the Society for the Protection of Monuments. Thanks to their efforts, the renovation of historic city centers, the restoration of palaces, manor houses, and religious buildings began, and historic garden cities were placed under protection. A particularly important legal measure was the requirement for municipalities to develop land use studies and spatial development plans, which helped prevent further chaotic urban expansion and contributed to preserving the historic character of many towns.

One of the most crucial directions in heritage restoration after 1989 was the revitalization of historic city centers. Many old towns, destroyed during World War II and neglected during the communist era, required urgent conservation work. A successful example of such a revitalization is the Warsaw Old Town, whose restoration was supported by UNESCO[29], as well as the historic centers of Toruń and Gdańsk, where old urban layouts were reinstated, and historic tenement houses were restored. Many cities took advantage of European Union funds to protect their historic districts and unique landmarks, such as Wrocław’s Centennial Hall or the underground market in Kraków. Numerous conservation projects, including the renovation of the Royal Castle in Warsaw and the Cloth Hall in Kraków, were financed by the European Regional Development Fund.[30] Meanwhile, the Norwegian Funds and the European Economic Area Financial Mechanism[31] enabled the restoration of many religious buildings, such as the Cistercian Monastery in Krzeszów, the Church of Peace in Świdnica, and wooden churches in the Greater Poland region, located in Brody, Bronikowo, Domachowo, Jeżewo, and Zakrzewo.

Revitalization efforts also involved restoring green spaces to their original historical form. Garden cities suffered from chaotic development and the loss of their original functions during the communist era. Thanks to new planning regulations and the support of local governments and community associations[32], further degradation of these towns was halted. Social organizations and civic movements played a particularly important role by engaging residents in efforts to protect cultural and natural heritage. Many local associations initiated projects to renovate historic parks, restore gardens, and rebuild traditional architecture. Their activism helped secure valuable green spaces and restore their role as centers of community life. New legal regulations in spatial planning now cover urban parks, squares, and gardens, ensuring better protection and preventing further development. In many cases, the determination of local communities enabled effective revitalization, raising historical and environmental awareness among residents.

The role of private investors in restoring Polish historical manors and palaces should also be highlighted. With the return of the market economy and changes in monument protection laws, it became possible to purchase or reclaim many historic properties. Examples of successful private restorations include the neoclassical manor in Żółwin, the Aida villa in Podkowa Leśna, and the Bishop’s Palace in Janów Podlaski. The Żółwin manor, associated with the Witaczek siblings, pioneers of the Polish silk industry, is now a private residence with hotel functions.[33] The wooden Aida villa, once the summer home of the Lipop and Iwaszkiewicz families[34], is now a private residence that actively hosts various cultural events. The Bishop’s Palace in Janów Podlaski[35] has been transformed into a luxury hotel with conference facilities, relaxation areas, and a spa. Thanks to numerous private initiatives, important historical monuments have been restored, along with their surrounding parks and gardens.[36]

However, the process of property restitution, which involved returning nationalized properties taken during the communist era, led to significant abuses. After 1989, restitution became a major legal and social issue. Unlike many Central and Eastern European countries, Poland did not pass a comprehensive restitution law, which meant that property claims were mostly resolved through lengthy court and administrative proceedings. The legal basis for restitution claims was found in the Civil Code, the Polish Constitution, and administrative law regulations. Former property owners (or their heirs) could demand restitution only if the expropriation decisions were made in violation of the law at the time. This applied to properties seized under the 1944 PKWN Land Reform Decree, the 1945 Bierut Decree[37] concerning Warsaw, and other nationalization acts.

The absence of a unified restitution law led to numerous controversies and abuses, especially in major cities, where cases of so-called “wild restitution” occurred—unclear transactions where property was taken over by “claims traders.” These individuals bought restitution claims—often at a fraction of their value—from heirs or former owners and then pursued them in court or through administrative proceedings.[38] In response, legal measures were introduced, including the 2015 “Small Restitution Law,”[39] which limited the restitution of Warsaw properties in kind and imposed stricter evidence requirements for claims. However, a comprehensive restitution law has still not been enacted, leaving many cases to be resolved through lengthy and complex court disputes.

Despite these controversial situations, the contribution of private investors to protecting Polish monuments after 1989 has been significant and invaluable. Many restored manor houses and palaces have once again become important landmarks in Poland’s historical landscape. Following old Polish traditions, many new owners have opened their gardens to the public, not just occasionally but regularly. Examples of such good practices include the Kazimierówka[40] and Radonie[41] manors near Warsaw.

Thanks to extensive national and international cooperation, Poland has managed to save a substantial portion of its national heritage, rebuild historic urban layouts, and restore the grandeur of former parks and gardens. The positive changes are easily visible. After years of neglect during the communist era, Poland’s rich cultural heritage has become one of the most important elements of national identity. Revitalization efforts continue, and one of the original ways to support them is the Open Gardens program and its flagship event—the increasingly popular Open Gardens Festival. This initiative primarily focuses on raising public awareness of the value of national culture in all its aspects, expressions, and manifestations.

The Impact of Open Gardens on Preserving Tradition

Created by Magdalena Prosińska and Łukasz Willmann, the Open Gardens Program is a key element of the broader process of rebuilding and promoting national heritage. Its main project, the Open Gardens Festival, has become a source of knowledge, inspiration, and engagement for local communities, encouraging active participation in protecting and showcasing the cultural and environmental value of their surroundings. This event allows people to rediscover the significance of historic urban, architectural, and landscape designs, as well as the beauty of old villas with their historic gardens and culturally significant sites. Through meetings, exhibitions, concerts, and workshops, festival participants gain a deeper understanding of their towns’ histories, the lives of former owners and creators of these spaces, and the importance of cultural and environmental preservation.

The festival contributes to restoring awareness of old Polish traditions while promoting historical landmarks, architectural and gardening styles, and local practices related to green space maintenance. A great example of the community’s commitment to preserving historical memory is the Turczynek villa and garden complex in Milanówek[42], one of many historic sites still awaiting restoration. This beautiful yet deteriorated site has long been in need of an investor willing to breathe new life into it. Festival events highlight the importance of such places in national heritage while engaging residents and local authorities in their protection, upkeep, and promotion.

The Open Gardens Festival also plays a crucial role in revitalizing social relationships. By bringing residents together around the cause of national heritage, it strengthens local identity and fosters community spirit. This initiative is part of a broader European movement aimed at preserving the cultural landscape of the continent. Thanks to the festival, Polish towns become part of an international network of places dedicated to promoting cultural and natural values. As such, the Open Gardens Festival is not just a heritage conservation effort but also a model of active civic participation, seamlessly blending tradition with a modern approach to cultural promotion and preservation.

Tomasz Domański

Owczarnia, Podkowa Leśna, 2025

Photos: Pixabay, Wikipedia, Cracow Drone

References

[1] In wealthy European countries, the culture of creating and maintaining gardens in private residences developed over centuries, primarily among the aristocracy, landowners, and affluent bourgeoisie. These gardens, beyond their aesthetic function, also signified the wealth and social status of their owners. A strong tradition of opening gardens was reflected not only in their number and stylistic richness but also in the commitment to sharing one’s assets with others.

[2] Baroque gardens, developed in the 17th and 18th centuries, were characterized by geometric layouts, symmetry, and precisely trimmed vegetation. The palace usually served as the focal point, with avenues, flower parterres, and hedges radiating outward, often complemented by fountains, sculptures, and scenic terraces. These gardens had a representational function and symbolized human control over nature. The most famous example is Versailles in France, while in Poland, notable baroque gardens include Wilanów Palace Gardens and the Branicki Palace Gardens in Białystok.

[3] Landscape gardens emerged in 18th-century England as a reaction to the formal Baroque style. Inspired by natural landscapes, they featured an informal layout, irregular paths, picturesque water bodies, and gently rolling terrain harmoniously integrated with the surroundings. These gardens often included clusters of trees and shrubs arranged to mimic nature, wide avenues, and romantic structures such as gazebos, bridges, and artificial ruins. Notable examples include Łazienki Park in Warsaw, Arkadia near the Nieborów Palace, and Stourhead in England.

[4] The Enlightenment dominated Europe mainly in the 18th century, fostering the development of science, rationalism, and political revolutions, including the French Revolution (1789–1799). The chaos and terror of this period led to the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, whose reforms, especially the Napoleonic Code, introduced modern legal principles, restricted feudal privileges, and strengthened the idea of a state governed by law. After Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815, the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815) restored monarchies and reinforced conservative rule. However, Napoleon’s era challenged absolutism and symbolically ended French dominance, influencing various fields of art, including garden design.

[5] Classicism was an artistic and intellectual movement of the 18th century, drawing inspiration from ancient Greek and Roman culture. It emphasized harmony, symmetry, simplicity, and restraint, opposing the decorative richness of Baroque and Rococo. Classical architecture featured regular proportions, colonnades, pediments, and clean lines, inspired by structures like the Parthenon. In literature and philosophy, classicism emphasized rationalism, morality, and universal ideals of beauty, while in music (Mozart, Beethoven), it sought clarity and balance. In architecture and garden design, classicism favored elegant simplicity and logical spatial organization, reflecting the Enlightenment values of reason and order.

[6] The National Gardens Scheme (NGS) is a British charitable initiative launched in 1927, allowing the public to visit private gardens in exchange for voluntary donations, mainly supporting healthcare and hospices. The program promotes horticultural arts, encourages knowledge exchange among gardening enthusiasts, and supports the preservation and development of private gardens. Every year, thousands of gardens across the UK open under the NGS, raising funds for charitable causes, making it one of Europe’s oldest and most significant initiatives of its kind.

[7] Rendez-vous aux jardins is an annual event launched in 2003 by the French Ministry of Culture to promote garden heritage and gardening arts. It takes place on the first weekend of June, involving hundreds of parks and gardens in France and other countries—both public and private. The festival features guided tours, gardening workshops, exhibitions, and expert meetings. Inspired by this initiative, similar events have emerged across Europe, promoting gardens as spaces for experience exchange, environmental education, and community integration.

[8] The European Union supports and promotes various international cultural events, including the European Capital of Culture, European Heritage Days, the Eurovision Song Contest, and the European Youth Week. Information about financial support opportunities for the cultural and creative sectors from 2021–2027 can be found in the CultureEU guide.

[9] The Polish aristocracy represented the highest social stratum of the nobility, mainly composed of magnates—wealthy landowners and politically influential families. Aristocratic titles such as princes, counts, and margraves were present, though they were not a formal requirement for membership in the magnate class. In the 18th and 19th centuries, under foreign rule, some Polish aristocrats adopted Western European customs, where hereditary titles conferred a higher social status.

[10] Opening aristocratic gardens in Poland served both prestige and propaganda purposes. Polish aristocrats and monarchs sought to portray themselves as enlightened rulers close to society, emphasizing their commitment to public welfare. Making green spaces accessible also had practical benefits, such as ensuring maintenance and preventing vandalism. Over time, private gardens evolved into public parks, becoming spaces for recreation, walks, and social gatherings. This transition laid the foundation for Poland’s tradition of public parks.

[11] The concept of the garden city was developed in the late 19th century by Ebenezer Howard, an English urban planner, who published the book *Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform* in 1898 (later republished as *Garden Cities of To-morrow*). Howard proposed a city model that combined the advantages of rural and urban life, where green spaces played a key role in urban planning. This idea was reflected in the design of many cities worldwide, including in Poland, where it inspired the development of places such as Podkowa Leśna, Milanówek, Komorów, Józefów, Konstancin-Jeziorna, and other towns outside the Warsaw region. The garden city concept contributed to the growing importance of green spaces in public areas and the transformation of private gardens into social and recreational spaces.

[12] The Saxon Garden in Warsaw, established between 1724 and 1748 for King Augustus II the Strong, was originally designed in the Baroque French style. It was destroyed during the Kościuszko Uprising in 1794 and suffered complete devastation. Between 1816 and 1827, it was transformed into an English landscape garden, following the prevailing trends in garden art at the time. After the destruction caused by World War II, the Saxon Garden was partially restored, preserving elements of both the French and English styles, making it a unique testament to the evolution of European garden art.

[13] The main initiator of the project to create Kraków’s Planty Park was Feliks Radwański (1756–1826), a professor at the Kraków Academy. In 1817, he convinced the Senate of the Free City of Kraków to protect the Barbican and parts of the city walls while converting the remaining ruins into green space. This initiative was driven by both aesthetic concerns and public health considerations. Work on the Planty began in 1820 and was financed by the municipal budget, private donors, and contributions from Kraków’s residents.

[14] The first allotment gardens in Polish territories emerged in the late 19th century, inspired by Western European models, particularly German *Kleingärten* and Scandinavian “workers’ gardens.” The oldest known allotment garden was established in Grudziądz in 1897 by the Society for the Beautification of the City. In 1909, one of the first workers’ gardens was created in Lviv, and in the following years, allotment gardens developed in other cities, including Poznań, Kraków, and Warsaw. Their primary purpose was to provide workers and urban residents with small plots of land for growing vegetables and enjoying outdoor leisure. During the Second Polish Republic (1918–1939), allotment gardens became more formalized and expanded on a larger scale. In 1927, the Association of Allotment Garden and Settlement Societies was established to coordinate their operation. These gardens often served not only practical but also social functions, hosting meetings and community events.

[15] Ujazdowski Park is one of the oldest and most representative parks in Warsaw, dating back to the late 19th century. It was designed between 1893 and 1896 by Franciszek Szanior, a renowned Polish gardener and landscape architect. Its layout followed the popular landscape style of the time, inspired by English parks, with picturesque paths, a pond, and lush vegetation. From the beginning, it served as a public park tailored to the needs of Warsaw’s rapidly growing population. During the interwar period, it was a popular spot for walks and leisure. The park suffered significant damage during World War II, but it was restored after 1945, with its historical layout reinstated in the 1950s and 1960s. Today, Ujazdowski Park, located near the Royal Route and Łazienki Park, remains one of the most beautiful green spaces in Warsaw, combining recreational, historical, and aesthetic functions.

[16] Stryiskyi Park in Lviv is one of the most significant and beautiful urban parks of former Poland, established in the late 19th century. It was designed by Arnold Röhring, a prominent Lviv landscape architect, who gave it the character of a picturesque English-style landscape park. The park was opened in 1879 on the site of former quarries and wastelands, which were transformed into a recreational space with numerous paths, ponds, scenic terraces, and diverse vegetation. In the early 20th century, it featured exotic tree species, a palm house, and exhibition pavilions built for the 1894 General National Exhibition. During the interwar period, Stryiskyi Park was a favorite leisure destination for Lviv’s residents and a symbol of urban greenery. After World War II, when Lviv became part of the Soviet Union, the park remained a recreational area, though some of its infrastructure was lost. Today, it remains one of the largest and most representative green spaces in the city.

[17] Skaryszewski Park, named after Ignacy Jan Paderewski, is one of Warsaw’s largest parks. It was established between 1905 and 1916, based on a design by Franciszek Szanior, a renowned landscape architect, who shaped it as a picturesque park inspired by English and modernist styles. Located on the right bank of the Vistula River, near Saska Kępa, the park is distinguished by its rich vegetation, numerous walking paths, scenic ponds, and garden sculptures. During World War II, the park suffered partial destruction, but after 1945, it was rebuilt and regained popularity as a recreational area for Warsaw residents. Today, Skaryszewski Park is valued for its diverse flora, picturesque landscapes, and architectural features. In 2009, it was recognized as the most beautiful park in Poland in a poll conducted by the Warsaw Friends Society and the *Urban Greenery* magazine.

[18] Ebenezer Howard (1850–1928) was a British urban planner and social reformer, best known as the creator of the garden city concept. His ideas were presented in the book *Garden Cities of To-Morrow* (1898), in which he described a vision of a sustainable city that combined the benefits of rural and urban life. Howard advocated for the development of small, self-sufficient communities surrounded by greenery, with well-planned residential, service, and recreational infrastructure. His concept was implemented in cities such as Letchworth Garden City (1903) and Welwyn Garden City (1920) in England. The garden city idea influenced urban planning in many countries, including Poland. The most notable contemporary example of Howard’s concept in Poland is Podkowa Leśna.

[19] The Polish People’s Republic (PRL) was the official name of Poland from 1944/1945 to 1989, functioning as a communist republic dependent on the Soviet Union. The PRL was established after World War II when power was taken by the Polish Workers’ Party (PPR) and later by the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR). The system was based on a one-party dictatorship, a centrally planned economy, and restricted civil liberties. Key characteristics of this period included Stalinism (1948–1956), workers’ protests (1956, 1970, 1976, 1980), the rise of the Solidarity movement (1980), and the Round Table Talks (1989), which led to the collapse of communism. In 1989, Poland began its political transformation, and the PRL was replaced by the system known as the Third Polish Republic.

[20] During the Polish People’s Republic (PRL), allotment gardens functioned primarily as Employee Allotment Gardens (*Pracownicze Ogrody Działkowe*, POD), established under the 1949 Act on Employee Allotment Gardens. These gardens were primarily intended for employees of industrial plants, public administration, and state enterprises, allowing them to grow vegetables and fruits and providing a recreational space in a time of limited housing availability. Management of these gardens was entrusted to trade unions, labor cooperatives, and workplaces. In 1981, the Polish Allotment Gardeners’ Association (*Polski Związek Działkowców*, PZD) was established to oversee their administration. In 2005, a law was passed that formally transformed existing gardens into Family Allotment Gardens (*Rodzinne Ogrody Działkowe*, ROD). However, a 2012 ruling by the Constitutional Tribunal found parts of the law unconstitutional, leading to the adoption of a new Family Allotment Gardens Act in 2013.

[21] Horticultural cooperatives played a significant role in food production and urban and suburban greening during the period of the Polish People’s Republic.** These were associations of farmers, allotment holders, gardeners, and beekeepers engaged in cultivating vegetables, fruits, and flowers for the market and local communities. Their operations were strictly controlled by the authorities and aligned with the broader policy of agricultural collectivization and the promotion of communal land management. From 1951, they operated as associations subordinate to the Central Agricultural Cooperative “Peasant Self-Help” (CRS “SCh”). After the political thaw of 1956, horticultural cooperatives regained some autonomy within the framework of agricultural cooperatives. Despite difficulties associated with the centralization and nationalization of the economy, they continued to function until 1989.

[22] The “Tag der offenen Gärten” (Open Gardens Day) is an annual event held in Germany, during which private garden owners open their spaces to visitors.** The initiative aims to promote gardening culture, facilitate the exchange of experiences among gardening enthusiasts, and inspire the creation and maintenance of green spaces. The event usually takes place on selected weekends in spring and summer, with variations depending on the region. Participants have the opportunity to admire diverse garden arrangements, ranging from traditional to modern, and connect with other gardening enthusiasts.

[23] The agrarian reform of 1944 was implemented under the decree of the Polish Committee of National Liberation (PKWN) on September 6, 1944.** Its goal was to confiscate and redistribute large landholdings and eliminate landed estates. Land exceeding 50 hectares (or 100 hectares in the “Recovered Territories”) was expropriated without compensation and distributed among landless and smallholding peasants. The reform covered approximately 6 million hectares of land, of which around 3 million hectares were allocated to peasants, while the remainder was retained by the state. The reform had a political character—it served to strengthen communist power, weaken the landowning elites, and garner support for the new system. In practice, it led to the disintegration of the traditional rural social structure, and the newly allocated farms were often too small and underfunded to sustain themselves. This situation later facilitated attempts to collectivize Polish agriculture.

[24] The nationalization decrees of Bolesław Bierut were a series of legal acts issued by the communist authorities of the Polish People’s Republic after 1944, aimed at transferring private property, industry, and land into state ownership. The most significant of these were: (1) The Decree of October 26, 1945, on the ownership and use of land in the city of Warsaw, under which the state took over nearly all built-up areas of the capital without compensation; (2) The Decree of January 3, 1946, on the nationalization of key sectors of the national economy, which brought most factories, mines, and private enterprises under state control. These decrees were tools of communist centralization, the elimination of private property, and the introduction of a centrally planned economy.

[25] After World War II, the communist authorities of the Polish People’s Republic, strictly subordinate to the USSR, systematically worked to eliminate the Polish aristocracy and bourgeoisie.** These groups were perceived as hostile to the new regime, as their existence contradicted Marxist ideology, which emphasized the dominance of the working class and peasantry. The process was carried out on multiple levels—through property confiscation, political repression, propaganda, and the creation of a new ruling class loyal to the communist government. One of the most striking measures in eliminating the old elites was the confiscation of land and private property. The 1944 agrarian reform decree led to the expropriation of the landed gentry, while the 1946 nationalization of industry resulted in the elimination of the bourgeoisie as a social class. Businesses, banks, townhouses, and land were seized by the state, leaving their former owners without means of livelihood. At the same time, the intelligentsia faced repression—academic, artistic, and cultural circles were strictly controlled and censored. Many aristocrats, industrialists, and pre-war intellectuals were accused of being “enemies of the people” and sentenced to imprisonment or execution in show trials. In place of the old elites, the communists systematically installed a new ruling class drawn from the working and peasant classes. This process was based on several mechanisms: (1) Promoting social advancement for individuals without adequate education but loyal to the Party; (2) Implementing extensive indoctrination in schools and universities while restricting access to education for individuals from “inappropriate” social backgrounds, such as the pre-war intelligentsia or aristocracy; (3) Using propaganda to legitimize social changes and construct a new hierarchy. Official narratives depicted the aristocracy and bourgeoisie as “parasites” and “traitors of the people,” while glorifying workers and peasants as heroes of the new order. Cultural productions—films, books, and plays—portrayed the old elite in a negative light while idealizing the new ruling class, consisting of Party activists and “class-conscious” common people. As a result, over the decades of the Polish People’s Republic, the historical elites were almost entirely eliminated or marginalized, replaced by a closed Party caste whose members passed power and privileges to their children, creating new “hereditary” elites. The consequences of this process are still felt today.

[26] In the Polish People’s Republic (PRL), urban planning in many cities was modeled on Soviet urban concepts, based on socialist realism and centrally planned economy principles.** This approach was characterized by monumental architecture, wide transportation arteries, distinct functional zoning, and residential districts designed as “microdistricts” (self-sufficient units with access to basic services). Post-war reconstruction and urban development in Poland were driven by ideological goals of industrialization, collectivization, and the removal of traces of the bourgeois past. Examples of Soviet influence on urban planning in Poland include: (1) The Marszałkowska Residential District (MDM) in Warsaw, designed after Moscow; (2) Nowa Huta—a model socialist city built from scratch; (3) In cities like Gdańsk, Wrocław, and Poznań, modernist and socialist-realist solutions replaced historic urban fabric with simple, functional housing blocks. After 1956, as socialist realism was abandoned, Polish urban planning gradually moved away from Soviet models.

[27] The transition from a centrally planned economy to a market system required a new approach to spatial planning, heritage protection, and historic site management. One of the key legal acts was the 1994 Spatial Planning Act, which introduced local spatial development plans as the primary tool for protecting historical buildings and cultural landscapes. This law granted municipalities greater autonomy in shaping space and preserving valuable sites. Another milestone was the 2003 Act on the Protection of Monuments and Monument Care, which precisely defined heritage protection principles, including registering buildings and areas as historical sites and placing them under conservation protection. Financial mechanisms were also introduced to support the renovation and restoration of monuments, allowing funding from the state budget, local governments, and international organizations. The implementation of strict urban regulations, the development of local heritage protection programs, and the increase in public awareness helped to better safeguard historical landmarks and preserve the unique character of historic spaces.

[28] One of the most important projects was the complete reconstruction of the Royal Castle in Warsaw.** While the exterior was rebuilt in the 1970s, it was not until the 1990s that its interiors were fully restored. At the same time, extensive conservation work continued at Wilanów Palace, restoring its Baroque interiors and gardens. Wawel Royal Castle also underwent thorough renovation, with damaged architectural elements restored and its historical interiors preserved. There were also initiatives concerning the Saxon Palace in Warsaw, destroyed by the Germans in 1944. The only remaining part of the palace was the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Although reconstruction was considered in the 1990s, concrete efforts began only in the 21st century. In 2021, an official project was announced to rebuild the Saxon Palace, Brühl Palace, and townhouses on Królewska Street.

[29] The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) was established in 1945 to promote international cooperation in education, science, culture, and heritage protection.** Poland has been a UNESCO member since 1946, with 17 sites currently listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

[30] The European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) was established in 1975 and is one of the main structural funds of the EU. Its aim is to reduce disparities in the level of regional development, especially in less developed areas. ERDF funds are allocated to investments in infrastructure, innovation, environmental protection, the development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and strengthening regional competitiveness. The fund plays a significant role in financing projects related to urban revitalization, cultural heritage protection, and the development of transport and energy sectors.

[31] The European Economic Area (EEA) Financial Mechanism, also known as the EEA Grants, is a financial support instrument provided by three countries: Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein. Its objective is to reduce social and economic disparities in Europe and strengthen cooperation between EEA countries. These funds are made available to EU countries with a lower per capita national income compared to the EU average, including Poland. The EEA Financial Mechanism often operates alongside the Norwegian Financial Mechanism—commonly referred to as the Norwegian Grants—which is additional support provided exclusively by Norway. Both mechanisms function in parallel but share the same goal: reducing inequalities in Europe and strengthening international cooperation. Poland is one of the largest beneficiaries of the EEA Grants, enabling the implementation of numerous projects, such as the revitalization of historical sites, modernization of cultural institutions, nature conservation, and the development of innovative technologies. In return for the provided support, donor countries gain access to the EU market under preferential conditions, despite not being EU members.

[32] The activities of local associations, such as the Socio-Cultural Society of the Garden City Sadyba, the Friends of the Garden City Komorów Association, the Podkowian Association, and the Friends of the Garden City Podkowa Leśna Society, have played a significant role in halting the degradation of garden cities around Warsaw. These organizations actively engage in protecting the cultural and natural heritage of their localities, promoting harmonious development and community integration. Through cultural and educational initiatives, as well as efforts to preserve the unique urban character, they counteract degradation processes, contributing to the maintenance of the historical and aesthetic values of Warsaw’s garden cities.

[33] The Żółwin Manor is a late-classical residence from the mid-19th century, designed by architect Józef Bobiński for Michalina Rzyszczewska (née Radziwiłł). Construction began in 1853, and the manor became a hub for social and cultural gatherings. Among its subsequent owners were Eustachy Marylski—a friend of Fryderyk Chopin—and the Szeller family, who established the surrounding park. During the interwar period, the manor belonged to Michał Natanson and later to Henryk Witaczek, who operated a silk production business there. During World War II, the manor served as a refuge for displaced persons and a meeting place for intellectuals such as Maria Dąbrowska, Ewa Szelburg-Zarembina, and Ferdynand Antoni Ossendowski. After the war, the estate gradually fell into decay until 2005, when it was restored by new owners. Today, the manor serves residential, hotel, and cultural functions, maintaining its rich historical legacy.

[34] Villa Aida in Podkowa Leśna was built around 1900 by Stanisław Wilhelm Lilpop, an industrialist and hunting enthusiast, as a summer and hunting lodge. After his daughter Anna Lilpop married writer Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz in 1922, the young couple moved into Aida, transforming it into a vibrant cultural center. Guests included members of the Skamander poetry group, such as Antoni Słonimski and Julian Tuwim, as well as composer Karol Szymanowski. In 1928, the Iwaszkiewicz family moved to their newly built home, Stawisko, and Aida changed owners, serving various residential purposes. Today, after renovation, it functions as a venue for cultural events, honoring its more than century-old history.

[35] The Bishop’s Palace in Janów Podlaski, also known as the Episcopal Castle, is a historic residence of the bishops of Lutsk, dating back to the 15th century. Between 1770 and 1780, Bishop Feliks Paweł Turski built a Baroque palace on the site of a ruined earlier structure, surrounded by a moat, an English-style park, and farm buildings. After the death of the last residing bishop, Adam Naruszewicz, in 1796, the residence became state property. In the 19th century, the palace served various functions, including as the headquarters of the famous Janów Podlaski horse stud farm. After World War II, the state took over the property, assigning it to the Janów Stud. In the 1990s, the palace fell into ruin, but in the early 21st century, it was restored and converted into a luxury hotel, combining historic architecture with modern technological solutions.

[36] Private investors often undertake the revitalization of deteriorated historical sites at their own expense, but they also benefit from EU financial programs and national funds designated for monument restoration. Their efforts contribute to saving many historic buildings that might otherwise fall into complete ruin.

[37] The Bierut Decree, issued on October 26, 1945, concerning the ownership and use of land in the capital city of Warsaw, was a legal act that transferred all land within the city limits to state ownership. Its official purpose was to facilitate the reconstruction of Warsaw after wartime destruction, but in practice, it led to mass nationalization of private property without a proper compensation system. The decree allowed former owners to apply for perpetual lease rights, but in most cases, applications were rejected or left unresolved. As a result, thousands of properties came under state control, and their previous owners often received no compensation.

[38] A shocking example of “wild reprivatization” is the case of Jolanta Brzeska, a social activist and co-founder of the Warsaw Tenants’ Association, who fought for the rights of tenants facing eviction due to the return of tenement buildings to private owners. On March 1, 2011, she was murdered. Her burned body was found in the Kabaty Forest near Warsaw. The investigation, initially closed, was reopened in 2016, but the perpetrators remain unidentified. Brzeska became a symbol of opposition to unfair reprivatization, and her memory has been honored through various initiatives, including naming a square in Warsaw’s Mokotów district after her.

[39] The “Small Reprivatization Act” is the colloquial name for the law of June 25, 2015, amending the Real Estate Management Act and the Family and Guardianship Code. Its goal was to regulate certain issues related to the claims of former owners of Warsaw properties expropriated under the so-called Bierut Decree of 1945. The law introduced pre-emptive rights for the City of Warsaw and the State Treasury in cases where claims to decree-affected properties were sold. Additionally, it allowed authorities to refuse restitution of properties used for public purposes, such as schools, kindergartens, and parks. These regulations aimed to limit “wild reprivatization” and protect public interest. However, the act did not comprehensively resolve the issue of reprivatization in Poland, providing only temporary solutions for selected Warsaw properties.

[40] Kazimierówka Manor is a historic residence located in Owczarnia, near Warsaw. Built in the late 19th or early 20th century, the manor is surrounded by a seven-hectare English-style park, filled with ancient trees encircling two picturesque ponds. In 2006, the estate was purchased by Marek Keller, a Polish art dealer and enthusiast of Mexican art. Thanks to his initiative, Kazimierówka underwent a thorough renovation and became a venue for exhibiting sculptures by Juan Soriano, a renowned Mexican artist. Today, the manor serves as an art gallery and cultural space, blending Polish traditions with contemporary Mexican art.

[41] The Radonie Manor, located in the Mazovian Voivodeship, is a historic residence with a rich history. The first records of the manor date back to a purchase-sale agreement from June 21, 1796. The current building was constructed in the first half of the 19th century, likely in 1842, by its then-owner Piotr Folkierski, who also established a brewery producing licensed Bavarian beer. After World War II, the manor was nationalized and housed a state-run agricultural farm (PGR), leading to its gradual deterioration. Following multiple unsuccessful restoration attempts, the manor was finally renovated in 2010 and now serves as a private residence and cultural venue.

[42] Turczynek is a historic villa and park complex located in Milanówek, in the Masovian Voivodeship. The estate consists of two eclectic villas, built between 1904 and 1905 by industrialists Wilhelm Wellisch and Jerzy Meyer, and designed by architect Dawid Landé. During the interwar period, Turczynek served as a summer residence for wealthy Warsaw families. During World War II, the villas were occupied by the Germans, and after the war, they housed, among other institutions, a training center for the Polish Youth Association and a pulmonary disease hospital. Today, the buildings are abandoned and in need of renovation. Surrounded by an expansive park with old-growth trees, Turczynek is an important part of Milanówek’s cultural heritage and is listed as a historic monument. Despite its deterioration and neglect, the site continues to attract history and architecture enthusiasts, who see its potential for revitalization and the restoration of its former grandeur.

© Copyrighted material – all rights reserved.

Copying without the author’s permission is prohibited.

For inquiries, please contact the author.